16 Sep Four Takeaways: Testing the Gender Competency Framework in the Philippines

Samantha Law, HRH2030’s gender lead, co-authored this blog.

________

HRH2030 validated the gender competency framework for family planning service providers in the Philippines in June and July of 2019. The team consisted of Samantha Law, HRH2030 gender lead; Andrea Poling, HRH2030 deputy project director; and Kent Tangcalagan, local gender consultant.

________

“We have to give the advantages and disadvantages of each [family planning] method so that the client can think about what is proper for them. Because it’s the clients’ choice.” This statement from a provider from the Cotabato Regional Medical Center really drove home the purpose of HRH2030’s gender competency framework for family planning service providers.

Around the world, gender norms influence the ability of couples and families to meet their family planning needs. But how does a service provider know what ‘gender sensitive communication’ really means to provide equitable services to women, men, girls, and boys, and even more so, ensure they are providing it? Explaining these complex and intangible concepts can be challenging for newly practicing providers, or experienced providers with unintentional gender biases, which is why HRH2030 developed the competency framework and technical brief. The next step was to ensure these concepts, which were developed and vetted in Washington, would translate to a global audience.

This summer, we spent a few weeks in the Philippines to validate this global resource with family planning service providers – what makes sense and what is more difficult to understand? – and to identify real world examples of gender competence to use in future training programs. Our team spoke with a range of stakeholders and service providers in three locations across the Philippines – Manila, Butuan, and Cotabato City – to seek varied perspectives throughout the country. In order to have a diverse and robust validation, we visited urban and rural clinics including predominantly Catholic, predominantly Muslim, and one area classified as GIDA, or a geographically isolated disadvantaged area.

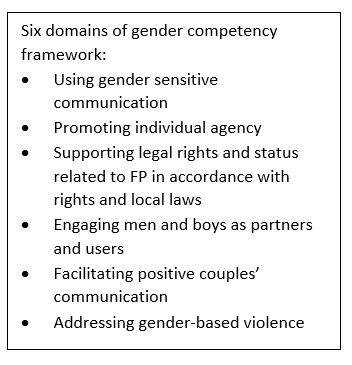

What did we learn through this validation? In discussing the six domains of the competency framework (see box at right) with 43 providers in 11 facilities, we had several key takeaways to advance gender competency:

What did we learn through this validation? In discussing the six domains of the competency framework (see box at right) with 43 providers in 11 facilities, we had several key takeaways to advance gender competency:

- Elements of gender sensitive communication are being practiced through quality counseling. Providers we spoke with most identified with the domain of using gender sensitive communication. This refers to a provider’s ability to transmit verbal and non-verbal communication in a way that promotes equality, regardless of gender. In the gender competency framework, the concepts of this domain align with providing quality counseling and ensuring voluntary and informed choice. The providers we spoke with understood and practiced these concepts, though may not have previously understood their significance through a gender lens. We heard several examples of this competency in action which all included the key theme of supporting the choice of the client regardless of gender, culture, or educational differences that could potentially impact access to information and services. For example, one provider in Agusan del Norte recognized how her role as a health worker could influence the equitable provision of services and shared, “I have more training and information, so it is my responsibility to communicate the information in a way they understand.”

- Concepts of gender competency are complex, but the competency framework and examples can break big concepts down into manageable actions. During interviews with key stakeholders in Manila, Dr. Alejandro San Pedro, chairman of the board of Midwifery for the Professional Regulatory Commission noted the complexity of translating big concepts of gender into meaningful actions for providers, asking “And how do you expect a 17-year-old midwife to understand all of this?” His question really highlighted the purpose the gender competency framework and spoke to the need for this resource. HRH2030 will be collecting examples of demonstrating gender competency and sharing them to help clarify terminology and provide ideas to make practicing gender competency more attainable.

- Male engagement is key but not always being practiced. Through our discussions, our team noted that while progress has been made in engaging men and boys in family planning, there is also work to be done. Engaging men and boys as users of and supportive partners in family planning is a widely recognized effective approach in many countries, cultures, and contexts. However, it is not always easy. In the Philippines, for example, engaging men in family planning is challenged by the belief that health centers are ‘women’s centers’ and therefore male engagement often relies on community outreach. Providers we spoke with in Cotabato City explained some tactics their clinics have used to engage men. These included providing family planning information at sporting events or other venues where groups of men gather; inviting satisfied male users of family planning to give testimonials; or simply asking a female client if her male partner drove her to the facility and, if so, would the woman like the provider to invite him in. Across interviews with providers, we consistently noticed a mismatch: while men are traditionally and typically thought of as primary decision-makers in regard to choice of a contraceptive method, the clients visiting the clinic were women.

- Integrating gender competencies into existing systems is critical for sustainability. Because the concepts of gender competency align with quality counseling, voluntarism, and informed choice, we also learned there is great opportunity to integrate gender competency training into existing pre-service and in-service training. When asked where providers learned key concepts in the framework, nearly all cited the government-led family planning competency-based training 1 and 2 which are required in-service training courses. When speaking with Attorney Carmelita Sison-Yadao, executive director for the Commission on Higher Education, she noted the possibility of infusing gender competencies in pre-service training, saying, “This can go into several programs. It can become a template for action providing guidance to using gender and development budgets.” HRH2030 is excited by the possibility of incorporating principles of the competency framework into existing systems to ensure consistency and increase sustainability.

Although this validation exercise provided incredibly valuable feedback for our global framework, it offered perspectives from a single country. To gain further unique viewpoints, HRH2030 aims to conduct a similar validation exercise, possibly in Ethiopia, before revising and finalizing the competency framework. We’re excited about additional resources in development, including a training to complement the framework, and a version of HRH2030’s lifecycle approach which incorporates gender competencies. Both will contribute to increasing family planning service providers’ understanding of how gender dynamics influence provision of equitable services. Stay tuned for more!

Photo: Samantha Law (far left) and Andrea Poling (second from left) listen to a group of health workers in the Philippines during the testing and validation of the HRH2030 Gender Competency framework. Credit: HRH2030, 2019.