22 Jul Presenting the 2nd Edition Gender Competency Brief for Family Planning Providers

Audio interview with Samantha Law Wilde, Manager, Global Health Division and Gender Specialist, HRH2030 (Running time 10:02)

Audio interview with Samantha Law Wilde, Manager, Global Health Division and Gender Specialist, HRH2030 (Running time 10:02)

As HRH2030 presents the 2nd edition of the Gender Competency Brief for Family Planning Providers, Communications Manager Catarina Cronquist takes a moment to discuss the brief and learn more about its significance to family planning service provision with Gender Specialist Samantha Law Wilde (pictured).

It’s exciting to have the chance to chat with you today as this marks the culmination of many months of work and travel for you. HRH2030 is so happy to launch the 2nd edition of your Gender Competency Brief for Family Planning Providers- congratulations! To kick us off, can share with us some background; tell us what this brief is and why it’s so important?

Thanks for the opportunity to talk about this. For a long time, we’ve known that gender is a big factor in decisions about family planning, both if a person should use family planning and then their ability to act on that decision, whichever they choose. We also know that providers play a big part in how clients get information and access to family planning services. But providers sometimes have their own perceptions of gender norms or are even inadvertently powerful and influence family planning choices beyond that of what the client initially was thinking. There’s a quote I read a long time ago from a health worker that I think sums it up really nicely and was a sort of the motivation of why this work came to be. It said, “We can’t give them birth control pills until they’ve had their first baby.”

I think that really classifies how providers sometimes might be thinking about their role in family planning. There’s not really a lot of guidance out there on how providers can be gender equitable. So, we created this set of competencies for providers so they can understand more about gender and power and deliver equitable services for every woman, man, girl, and boy who wants family planning or to talk about it.

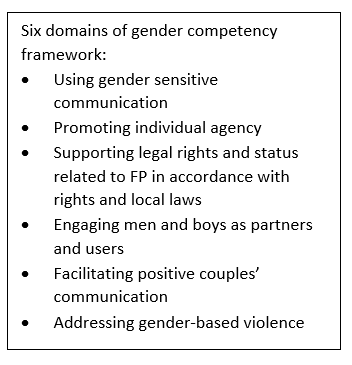

Can you explain for us the gender competency wheel and give us an example or two of what it means to be gender competent?

The gender competency wheel is our quick visual for gender competency. It’s made up of six domains that each form being gender competent and work together:

The first and the most fundamental is using gender sensitive communication. This refers to recognizing that there’s different verbal and nonverbal ways to communicate with a person based on their gender to help them make voluntary and informed choices about family planning.

The first and the most fundamental is using gender sensitive communication. This refers to recognizing that there’s different verbal and nonverbal ways to communicate with a person based on their gender to help them make voluntary and informed choices about family planning.

The next component is promoting individual agency, which really speaks to the idea that family planning is an individual choice and providers can support clients to make those choices. It might look different for men and women and based on the cultural context and norms in that society.

Next, we go to supporting legal rights and status related to family planning in accordance with rights and local laws. An example here is a provider who knows that no spousal consent is required, so she doesn’t ask those kind of questions when she’s talking to a client.

The fourth domain is engaging men and boys as partners in users. While all the previous domains refer to both men and women, we know that in reality the majority of providers when they’re talking to clients, it’s female clients. Engaging men and boys is incredibly important in family planning, so it’s essential to call this out, as providers don’t always think of men as clients and don’t feel comfortable talking to them about family planning.

The next domain really builds right on this. It’s facilitating positive couple’s communication and decision-making. This domain is all about helping the provider to navigate the conversations between couples to reach shared decision-making. It can happen both when the provider has the opportunity to talk about family planning with both members of a couple, but also when the provider is only talking to one person—which we recognize might be more common in our current situation—and coach that individual through having conversations with a partner at a later time.

Finally, all these competencies really culminate in our last domain which is addressing gender-based violence (GBV). Unfortunately, this is a part of family planning services and, time and time again, we hear that family planning providers don’t have the skills and knowledge to deal with gender-based violence, even when they’re confronted with it. While clinically addressing gender-based violence takes extra training and goes beyond these competencies, a gender competent family planning provider knows how to deal with GBV from the standpoint of knowing what it is and how to provide the resources and appropriate referrals.

So these are the six domains that make up the gender competency wheel and the components of gender competency.

What are some key updates we can expect to find in this 2nd edition?

The second edition is really exciting because it incorporates some of our experiences with testing out the competencies in both the Philippines and Ethiopia. We have updates across the board that reflect the realities of service delivery in those two contexts and we think speak to a lot of different contexts around the world.

The second edition is really exciting because it incorporates some of our experiences with testing out the competencies in both the Philippines and Ethiopia. We have updates across the board that reflect the realities of service delivery in those two contexts and we think speak to a lot of different contexts around the world.

Perhaps most exciting to me is that we’ve been able to pull that into a lot of different examples, which really brings to life the competencies and gives a concrete way to visualize how you might demonstrate these competencies. So, across every domain we have examples that we’ve been able to pull out of the Philippines and Ethiopia. Both good examples of demonstrating gender competency and a few that demonstrate what not to do, which I think is really helpful.

And then, finally, the other big update here is we have built off of HRH2030’s overall health worker lifecycle approach and made a version for gender competency since we’ve been focusing on the competencies of gender competence and how that might fit into things like pre-service education. But gender competency can go throughout the whole life cycle; it can be part of licensing, it can be part of supportive supervision, or job descriptions, and so we have a great infographic that explains all the different places where gender competency could be in the health system.

HRH2030’s Samantha Law Wilde (left) and Andrea Poling (center) speak with health workers in the Philippines during the testing and validation of the HRH2030 Gender Competency Framework.

Did you have any eye-opening moments when in the Philippines or Ethiopia—did you notice some things you hadn’t considered before in regards to family planning service provision?

There were a lot. In the Philippines, one of the things that really struck me was the topic of male engagement and how a lot of the time there’s this belief that health centers are women’s centers and it’s not a place for men. But at the same time, there’s this juxtaposition because men are traditionally thought of as the decision-makers even when it comes to contraceptives, but women are coming to the clinics. And so there’s this big mismatch and so that reinforces that this domain of engaging men and boys in family planning is really critical because there’s a lot going on even before a client might come to the clinic to talk about family planning and just reinforce it. This is an essential domain to call out.

In Ethiopia, there were two things that really stood out to me. One was the competency framework is meant to be sort of blind of any particular cadre of health worker. It can be for nurses, doctors, midwives, but we weren’t necessarily thinking of some of those less traditional cadres and someone pointed out to us that we really need to encompass a lot of different people so guards, receptionists, cleaning staff all really play a role in how a person feels coming into an environment and whether they feel welcomed and respected.

The other piece that really stood out to me in Ethiopia was a difference from what we found in the Philippines. When we tested out the competencies in the Philippines, the competencies in the gender-based violence domain really resonated with providers and we didn’t have a lot of revisions to make after that. But in Ethiopia, the system for dealing with gender-based violence is a lot less sophisticated and providers had a lot of confusion in thinking about some of the gender-based violence competencies, so we realized we needed to take it down to an even more fundamental level. For example previously, the first competency had been that a person can list the common signs and symptoms of GBV or GBV risk factors, and we realized we needed to get even more elemental and really bring in that a person recognizes the definition of GBV in the concept of GBV. So that was very eye-opening.

To conclude our chat today, can you share with us some forward-looking thoughts? What is the change you hope to see from enhancing gender competency in family planning service providers?

I hope that this provides another tool or another angle to improve the quality of family planning conversations and creates more access for people around the world. I think family planning providers are doing incredible work in challenging circumstances, and they don’t always have the resources to think about different ways to communicate and reach their clients effectively. Our next steps on this are creating a training on these concepts, which I think will bring even more opportunities for learning and understanding the gender competencies and eventually improving gender equality and reproductive health outcomes.

Header photo: Samantha Law Wilde (left) speaks with a health worker in Ethiopia during the testing and validation of the HRH2030 Gender Competency Framework. Credit: HRH2030, 2020